There is no liquid water on Mars. The atmosphere's too thin for it to subsist on the surface of the planet. There's water ice, beneath the surface of the planet and crusted beneath carbon dioxide ice at the poles of the planet, but if there ever was any liquid on Mars' surface, it was in the past.

Not everyone's convinced that there was. And there's still a lot of information being gathered. But on Mars, there are channels carved into the surface of the planet, many of them comparable in size to the Grand Canyon. But even here on Earth, scientists are unsure about how the Grand Canyon formed--it's too huge to be explained away by the ordinary reasons for canyon formation: water carving a path through stone, wearing it away. If it was water that made it, we've halted that process by damming the Colorado river, which traps sediment and controls flooding, and by consuming too much water for agriculture and industry.

It's possible, however, that these channels were carved by lava. The streamlined islands that some of the larger ones feature, showing flow direction, aren't necessarily a definite sign of water; and it would take a lot of water to carve the channels in question. (If Mars' South Pole melted, there would be enough liquid water to cover the surface of the planet a few feet deep.) There are certain ripple patterns in the rock at the bottom of certain canyons that seem to indicate lava flows passing through.

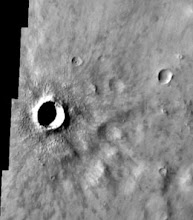

Certain craters, such as the Bacolor Crater in Utopia Planitia, show a dramatic ring of materia ejecta, or material sprayed around the crater itself by the force of the impact, that indicates a phreatomagmatic explosion, which would be caused by a crater impacting into water or possibly ice, if it melted fast enough. Instead of the usual dust and rock fragments that would be ejected from a normal impact crater, there's a much larger pattern of more liquid debris.

There's a certain land form known as "chaotic terrain" on Mars, often associated with the beginnings of channels. It's jumbled-looking (chaotic), like a patchwork of ups-and-downs, where portions of land collapsed inwards. It was caused by magma coming closer to the surface of the planet, heating subterranean ice until it melted almost instantaneously, leaving the ground collapsed and webbed behind it. Because it seems to have formed channels, it couldn't have evaporated instantly, the way water would today: it had to have persisted, in a liquid state, for at least a little while.

There's recent evidence of hematite, an iron-rich mineral that can only be formed in warm, still water, on Mars. It's only present in tiny nodules in the soil, but that it's there at all is strong evidence for water. How else would it have gotten there? And Mars certainly has enough iron. The red color in the soil is iron oxide, or rust, coloring the pale basaltic dust.

Finally, there are certain surfaces on Mars that are newer than the others. The lava flows surrounding the biggest volcanoes are one spot. The insides of some of the newer meteor craters. The largest area is north pole of the planet and the area surrounding it, a series of low plains. It can't be a fresh surface because of lava flows, because it's lowered, not raised. It looks a lot like a dried-up ocean.

But we have no way of knowing. And even if we do find ever conclusively prove that there was liquid water on Mars, once upon a time, it's still no guarantee that there was ever life on Mars, just like there's no evidence that the liquid water ocean on Saturn's moon Enceladus means that there's life there.

Friday, September 4, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment