On Mars, there's a canyon longer than the United States is wide. You could put a state on the bottom of it, and it would disappear. There are mountains three times as tall as Mt. Everest, and craters the size of continents. Mars itself is smaller than the Earth, one fourth to one third the diameter of our own planet and with only one tenth as much mass, but the features are exaggeratedly huge.

The biggest of these titantic cracks and features are because the planet is so small. Olympus Mons, the biggest mountain in the solar system (twenty-seven kilometers high, and big enough that it needs to be calculated for when they're programming the orbits of satellites) is now extinct, but it was once a vast volcano, clustered with three others; together, they caused lava flows that cover almost a fifth of the planet's surface. They make up four of the five largest mountains.

They are all volcanic, because Mars doesn't have crustal plates. Since the smaller planet, with a thinner atmosphere--often one one-thousandth of Earth's--couldn't insulate effectively against the chilling vacuum of space, Mars' molten core cooled faster than Earth's has, before the drag of magma was able to break up the planet's solid surface into plates. Or maybe it's because there wasn't enough magmatic force to build up the momentum required to fracture the surface so effectively--either way, Mars is one solid sheet of rock, not an ever-shifting, recreating sheath of a puzzle, like Earth.

The biggest valley on Mars, the Valles Marineris, is because of early volcanic action, before the planet cooled to nothing more than an orbiting rock. Valles Marineris is rift, visibly different from the sinuous valleys carved onto the planet's surface by lava, water or some other liquid. Valles Marineris is located near the volcanoes, in an area visibly raised from the rest of the planet: it was pushed outwards by magma rising up underneath it, creating this volcanic locus. It was enough to start fracturing the planet's crust--it was starting to form into crustal plates, but it wasn't quite enough. Instead, it stopped, in a gash carved across the planet, a scar that could span the United States.

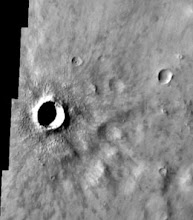

Because there are no plates, and therefore no plate tectonics to constantly renew the surface of the planet, swallowing and recreating land constantly in a dance that plays out under our very feet on Earth, the surface of Mars is far more ancient. Again, this has caused scars: the landscape is littered with craters, ranging in size from ones you could step across to craters more than two thousand kilometers across: Hellas Planitia is a vast, ancient impact crater with a diameter more than half of the United States' width: from San Francisco to Cincinnati.

Meteors hit only rarely, and it's only because of the unimaginable age of the exposed planetary surface that it's so covered with the pockmarks of meteor craters. If Earth's surface wasn't constantly refreshed, it would look similar, or maybe only a little cleaner, because the thicker atmosphere would help protect a little against incoming meteors. The planets are comparable ages: four and a half billion years old.

Other than the meteors, and the winds that stir the Martian dust, there is very little movement on the planet's surface. The volcanoes have all gone cold; there is no liquid water, only slowly evaporating ice. Nothing grows or lives. The only regular disturbances are dust storms and landslides along the edges of the chasms, shifting around the fine, powdery dirt. The dust devils are usually relatively small, forming inside of craters where the air heats unevenly and momentarily stripping away the dust before it forms again, but sometimes they grow much larger, turning into dust storms that can envelop half the planet, thousands and thousands of miles across, like a grossly exaggerated, vast hurricane.

In many ways, Mars is an unextraordinary planet. It is not the largest (Jupiter) or the smallest (Mercury), not the coldest (Uranus) or the hottest (Venus). It has two small, irregular moons, glorified asteroids who got caught up in the planet's orbit: it's much like our planet, only with less variation. There are two poles, both with large amounts of water ice capped with dry ice. Liquid water would sublimate instantly on the surface of Mars, because of the thinness of the atmosphere. The temperature ranges from negative two hundred thirty degrees to sixty-eight degrees, depending on the location, time of year and season. One day on Mars is half an hour longer than a day on Earth, and a year is about twice as long. Again, there are planets with greater extremes on either side.

Still, Mars has captured the human imagination. There are myths and stories about Mars ranging from the oldest civilizations to today: the word "Martian" is almost interchangable with the word "alien." People are captivated with the search for life on Mars. It's the best-studied planet in our solar system, second only to Earth. NASA is working on a manned mission to Mars. Many of the channels on Mars are named after the words cultures have held or hold for the planet: Al-Qahira, Aries, Auqakuh, Bahram, Harmakhis, Her Desher, Hrad, Huo Hsing, Kasei, Labou, Ma'adim, Maja, Mamers, Mangala, Marikh, Marte, Mawrth, Nirgal, Shalbatana, Simud and Tiu Valles, all meaning the same thing in twenty different, disparate languages and cultures, spread across the planet.

Wednesday, September 2, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment